In 2017 Uwe Schögel, the Executive President of the European Society for the History of Photography (ESHPh) invited me to be the Guest Editor for the PhotoResearcher, the society’s quaterly. The theme of the issue – Photography & Film – had already been decided, but I had a completely free hand in all matters of content. This gave me the opportunity both to choose the authors myself and to determine the range of topics. Although it is not specifically stated on the cover, I also co-authored an article with Brian Pritchard in addition to the foreword, which I have also posted below.

Editorial

by Martin Reinhart

Almost 90 years ago, in the summer of 1929, the tradition-shattering Werkbund exhibition Film und Foto (FiFo) started its triumphal tour throughout Europe.[1] First in Stuttgart and later in Zurich, Berlin, Gdansk, Vienna, Zagreb and Munich, the camera for the first time manifested itself as the mediator of the so called »New Vision« (fig. 1). The show caused a sensation in the national press, as well as in foreign countries and – as a result – the displayed cinematic and photographic experiments soon became renowned as the epitome of avant-garde production and modernism throughout the world. Next year, in 2019, a big FiFo jubilee exhibition will tour through Germany[2] and we also want to take the upcoming anniversary as a motive and starting-point to once again investigate the relationship between photography and film – both in their historical dimension, as well as in their past and current practice and technology.

One could argue that the radical program of the FiFo – based as it was on the analogue materiality of celluloid – has lost some of its initial urgency and that the principles of film-based photography and cinematography might be seen as atavistic models unfit to grasp and dis-cuss the immersive visual media of today. But now – as in 1929 – the main shift is not the one between rivalling technologies, but towards new and unforeseen ways in which still and moving images spark our imaginations and enrich our perception. So, rather than emphasizing technical and media-specific dividing lines, we want to carry on the FiFo’s revolutionary spirit by focusing on the multifarious quality of the related media and exploring their visual and technical transitions.One key factor in this regard is the accessibility and omnipresence of the camera and the way it became an integral element in our lives. The starting point of this development can be traced back to the beginning of the 20th century but it turned into a mass phenomenon at precisely the same time as the avant-garde proclaimed a counter-culture of new visual expressions.

(Fig 1) Poster for Film und Foto, 1929. Offset lithograph 33 x 23 1/8” (84 x 58.5 cm). The poster was designed by German photo-journalist Willi Ruge (1892-1961) and used a 1927 photograph of his friend, photographer Arno Böttcher

In the 1920s, amateurs and artists – the “Raphaels without hands”[3] as some called them – understood themselves as the antipodes to the “professionals” and postulated the democratisation of image production. Franz Roh conjures up this radical shift in media politics in the manifesto-like introduction to his book photo-eye[4] as follows:

“the appliances of new photographic technique are so simple that in principle everybody can handle them. the technique of graphic art [...] was so complicated and slow, that up to the present time people were met with, who though absolutely pos-sessing the visual power of forming, yet had neither leisure nor perseverance nor skill to learn the way of realization. the relation between conception and the me-dium of expression was too complicated. from this viewpoint it is characteristic that in this book non-professionals get a hearing. [...] only when the technical media have become so simple that everybody can learn to apply them, will they become a keyboard for the expression of many. the statement is right, that not to be able to handle a camera will soon be looked upon as equal to illiteracy.”[5]

In this way – fuelled by easy-to-use technology and affordable film – a dream came alive: a utopian vison of free and self-determined media producers, liberated from canonical tradi-tions, exchanging without the regulations of a state or the industries.

In this context, Noam M. Elcott’s opening article The Cinematic Imaginary and the Photographic Fact: Media as Models for 20th Century Art provides an overarching introduction to this vast field and, in a schematic yet rigorous fashion, locates the centres of gravity for interwar and post-war avant-garde experiments in cinema and photography or – as Elcott calls it – the cinematic imaginary and the photographic fact. Including neighbouring disciplines like painting and literature in his argument, he succeeds in showing how diversified and multi-faceted this entwinement was from the very beginning. And, by referring to the then new and ambiguous artist-figures like the photographer-filmmaker, the photo-monteur and the artist-engineer, he points at the intimate personal, theoretical and aesthetic overlaps which are so characteristic for this inter-medial field.

One of these central figures was avant-garde artist and Bauhaus teacher László Moholy-Nagy. Not only was he an influential practitioner and a theoretician of experimental art but, through his far-reaching international contacts, also an important promoter and contact point for the widespread and often rivalling avant-garde movements of his time. Moholy-Nagy was one of the curators for the FiFo exhibition and his selection showed an almost boundless curiosity for all past, present and future applications of photography and its in-teraction with other media. One of his particular interests lay in the anonymous and tech-nical imagery including x-rays, micro/macro photography and photogrammetric images. In the preface to the 1927 edition of his book Painting, Photography, Film[6] he summarizes his views as follows:

“The camera has offered us amazing possibilities, which we are only just be-ginning to exploit. The visual image has been expanded and even the mod-ern lens is no longer tied to the narrow limits of our eye; no manual means of representation (pencil, brush, etc.) is capable of arresting fragments of the world seen like this; it is equally impossible for manual means of creation to fix the quintessence of a move-ment; nor should we regard the ability of the lens to distort — the view from below, from above, the oblique view — as in any sense merely negative, for it provides an impartial approach, such as our eyes, tied as they are to the laws of association, do not give. [...] Although photography is already over a hundred years old — it is only in recent years that the course of develop-ment has allowed usto see beyond the specific instance and recognise the creative consequences. Our vision has only lately developed sufficiently to grasp these connections.”

In her article Black Box Photography Katja Müller-Helle explores this interest in technical images, which she extends to the photographic and filmic practices of experimental filmmaker Harun Farocki. In this way, she explores the avant-garde’s scope in both directions – discussing present systems of surveillance, as well as looking back to the begin-nings of automatic image acquisition and reading of images that began in the mid-19th century. Introducing the planchette photographique – one of the earliest examples of a photogrammetric panorama camera from the 1860s – Müller-Helle shows how this specific field of photography became part of a modernist vision that linked technological progress to the not-yet-thin kable.In 1929, three programmatic books were published in the context of the FiFo exhibition: Franz Roh’s and Jan Tschichold’s already mentioned Foto-Auge (Photo-Eye), Werner Gräff ’s Es kommt der neue Fotograf (Here Comes the New Photographer, fig. 2 ) and Hans Richter’s Filmgegner von Heute – Filmfreunde von Morgen (Today’s enemies of film – tomorrow’s friends of film, fig. 3). The two books were drafted and advertised as the accompanying text and the accompanying images of the exhibition and were released simultaneously and in the identical style and finish by the same publisher.[7]

(Fig 2) To the left: Page 72 from Werner Gräff ’s book Es kommt der neue Fotograf with photogrammetric pictures by Carl Hubacher, Berlin 1929. (Fig 3) To the right: Page 7 from Hans Richter’s book Filmgegner von Heute – Filmfreunde von Morgen, Berlin 1929

While Foto-Auge and Gräff ’s book exclusively focused on new developments in photography,[8] Richter’s publication is one of the first that tries to translate cinematographic devices into graphic layout by using 35mm cine-filmstrips and individual frame enlargements. In the preface to his book, Richter even gives an elaborate explanation of how the illus-trations are meant to emulate movement, filmic rhythm and cross-dis-solves. Today, Richter’s book is seen as a role model for the whole genre of cinematic photo books to follow. In his article Under A Certain Influence Roland Fischer-Briand discusses the history and diversity of this field and gives examples for the articulated forms of film- and cinema-related photo publications throughout the 20th century.

Richter’s book is also significant for another reason since its author was the curator of the extensive film program that accompanied the FiFo ex-hibition. In the time prior to the show the works of the avant-garde ran under various terms such as Absolute Film (fig. 4), Abstract Film, Cinéma Pur, Futurist Cinema and Surrealist Film but, due their ambiguous formats, these films have been seen more as isolated individual experiments than as-sociated with a specific genre or artistic movement. Being an experimental filmmaker himself, Richter compiled international feature-length and short films and bundled them in 15 events which were shown in a Stuttgart cinema and accompanied by film lectures. Today, his ground-breaking FiFo program is not only considered the forefather of all film festivals, but also the starting point of an identity-generating tradition of experimental film.[9] Inspired by, and as a direct result of, Richter’s program private and politi-cal film clubs were formed all over the world. This movement was driven by the cineaste’s enthusiasm for the non-commercial art film and made possible by the introduction of affordable amateur-format film material by companies like Kodak and Pathé.

(Fig 4) To the left: Menno ter Braak, De Absolute Film, No. 8 van de serie monografieen over filmkunst, Rotterdam: W. L. & J. Brusse 1931. Cover design by Piet Zwart. Private Collection. (Fig 5) To the right: Cover of Soviet Cinema No 1, Moskau 1927. Layout by Varvara Stepanova depicting Russian avant-garde film maker Dziga Vertov shooting with his Debrie Sept camera on roller skates

The new film stock helped to create new and independent distribution networks and led to the development of easy-to-use still and movie cameras. This equipment was originally targeted at the amateur market, but soon also adopted by film makers like Dziga Vertov, Able Gance or Joris Ivens. In particular, the introduction of lightweight 35mm still cameras such as the Leica, and hybrid cine-cameras like the Debrie Sept (fig. 5), played just as important a role in revolutionizing photography and avant-garde and amateur film making. In his article Sensitive Strips Brian Pritchard illuminates the origin and the history of the 35mm celluloid filmstrip and its mutual usage in photography and film. By discussing the technical dif-ferences and similarities he, at the same time, tells the parallel story of the medias’ intertwined development and their social implementations. When, within the specificities of cinematic flow, can individual film-frames become photofilmic images? And how can a single image turn into a narrative dispositive? These seemingly simple, but still highly relevant fundamental questions are investigated and reflected in two articles that are not so closely related to the historical FiFo exhibition, but still owe a lot to its vivid spirit. The figure of thought the authors introduce here is using the example of animation in its widest sense in order to open up a productive discourse of the intertwined media. (Fig. 6) In this way, a theoretical toolset is provided to unravel the braiding of the fictional, the attractional, the formal, the philosophical and the technological aspects of the cinematographic dispositive.

In her essay Photofilmic Time Machines researcher and artist, Lydia Nsiah, explores the field of ‘photofilm’ – a term that has been introduced to describe a specific art form that uses series of still photographs to create transitional and interfering phenomena of time (re-) production and perception. After giving a brief introduction to the history of photofilm, Lydia Nsiah sets out her outline of the disruptive potentials inherent in the photofilmic drawing on three contemporary art works. And, in his precise study Stroboscopic Revelations in Blade Runner, Barnaby Dicker focuses on yet another aspect of animation – namely, how stop-frame cinematography may be taken as a meeting point between photography and cinema-tography. He proposes a deeper reading of the famous photo-analysis scene in Ridley Scott’s science-fiction 1982 feature film Blade Runner – a scene that is never fully photography or cinematography, but oscillates variably between the two – by following its elliptic path into a convex looking-glass.

Footnotes

[1] Outside Europe, the exhibition was shown in Tokyo (April 1931) and Osaka (July 1931).

[2] The exhibition curated by Kai Uwe Hemken will start in Düsseldorf at the beginning of 2019 and then be shown in Darmstadt before finally coming to Berlin in September of the same year.

[3] Franz Roh uses this figurative expression in the preface of Foto-Auge, but initially it was not associated with photography. The dictum first was used in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s play Emilia Galotti (1772) in an argument discussing the conceptual and manual aspects of painting.

[4] Franz Roh, Jan Tschichold, Foto-Auge. 76 Fotos der Zeit, Stuttgart: Fritz Wedekind, 1929.

[5] Roh, Tschichold 1929 (reference 4), 14. English translation from the printed book.

[6] The German first edition was published as No 8 in the series of the Bauhaus publications under the title of Malerei, Fotografie, Film (Bauhausbücher, 8.) by Albert Langen Munich, 1925. Translation from the printed English version of the book.

[7] The two books were introduced in Die Form No 10 in May 1929 as part of the promotion for the FiFo exhibition. The Werkbund magazine was also published twice a month by the Hermann Reckendorf publishing house.

[8] Franz Roh ends his preface of Foto-Auge with the following statement: “The most important utilization of photography, the cinema — a marvel that has become a matter of course and yet remains a lasting marvel —is not within the province of this book. we are concerned but with the statically fixed, with situations that merely pretend dynamic, while in the cinema, by addition of static situations, real dynamic rises, questions of form here enter an entirely new dimension. Roh, Tschichold 1929 (reference 4), 18.

[9] I want to thank Thomas Tode for providing so much helpful information on the FiFo film program.

Title Ilustration: Film laboratory scene identifier, single 35mm frame from Chad Chenouga’s 2001 feature film 17, rue Bleue. Collection Martin Putz, Vienna. These markers normally are invisible for the cinema audience but an essential information during the development and printing process of analogue film - used for example to synchronize the images with the optical soundtrack.

Sensitive Strips. Motion Picture and Still Photo Film Formats

by Brian Pritchard and Martin Reinhart

In 1838 – one year prior to Daguerre’s first public demonstration of his process of photography – Sir Charles Wheatstone published a groundbreaking paper on stereoscopic vision. His interest in this field can be traced back to the early 1830s, to the very period in which the persistence of vision was also first investigated, described and scientifically explained by various scholars. Around the same time and parallel to Wheatstone’s Stereoscope, a number of optical toys using the stroboscopic effect were developed and introduced; among them, the Phénakisticope (1832) by Joseph Plateau, Simon Stampfer’s Optical Magic Discs (1832) and – at least as a concept – William George Horner’s Zoetrope (1834).[1] So, within the range of a few years, it became possible to trick two essential aspects of human vision and build devices that would give the eye an illusion of depth and motion. What would have been more desirable and logical than to combine these new possibilities with the photographic image? In the case of stereography, this task was achieved almost instantly – with the latter, it took some forty years. The reason for this latency is easily explained: whereas, even the long exposure time of a Daguerreotype was no obstacle for a photographic stereogram, it made recording moving objects completely impossible. The first Chronophotographic experiments had to wait until the invention of the gelatin dry plate by Richard Leach Maddox in 1871 which allowed much faster exposure times. Together with the introduction of the flexible celluloid film in 1888, the way for cinematography was finally paved. But let’s stop at this very point in history and have a closer look at how the theoretical and practical concepts of the 1830s finally merged with photography.

(Fig 1) Camel Running. Complete sequence of 24 single frames for Ottomar Anschütz’s Electrotachyscope. 6x9 cm celluloid film sheet transparencies, early 1890s. The same image series has been released on a paper strip for the Anschütz Zoetrope

The pre-photographic solutions to creating an illusion of motion can be divided into three basic principles: the wheel, the flipbook and the ribbon. And each single one of these principles was tested and utilized almost simultaneously as soon as instantaneous photography was at hand. Starting with Eadweard Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope in 1879, several new viewing machines using rotating discs with transparent phase images were introduced. The stroboscopic effect that is essential for creating the illusion of movement was produced by mechanical shutter mechanisms or electrical flashes. Combined with a lantern, some – such as Georges Demeny’s Phonoscope (1892) – were built as projection-devices for bigger audiences; others, like Ottomar Anschütz’s Electrotachyscope (1891), provided entertainment for single viewers (fig. 1). Regardless of their design, all these devices could only display a fairly short, seamlessly looped movement. Due these restrictions, the public fascination for these machines soon faded.

The Mutoscope (fig. 2), introduced in 1894, worked on the same principle as the flip book and extended the viewing time to about one minute. The individual image frames were conventional black-and-white, silver-based photographic prints on tough, flexible opaque cards. Rather than being bound into a booklet, the cards were attached to a circular core. One of the interchangeable reels typically held about 850 cards. Similar to Anschütz’s Electrotachyscope, these machines were coin-operated and electrically illuminated. The Mutoscope was invented by W.K.L. Dickson and Herman Casler, both early film pioneers and founders of a syndicate that later would become the very successful American Mutoscope and Biograph Company.

(Fig 2) View of the drying and retouching room of the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company. One viewer is displayed in the foreground. Illustration from around 1895. From: Albert. A. Hopkins. Magic: stage illusions and scientific diversions, including trick photography. New York: Munn & Co, 1897, p. 503

Prior to his business with Casler, Dickson worked as the company’s photographer at Thomas A. Edison’s laboratory in Menlo Park. There, he soon became a driving force behind the one development that would set a worldwide standard for motion pictures and still images alike: the 35mm filmstrip. In his book The Life and Inventions of Thomas Edison,[2] Dickson gives a detailed description of the experiments he conducted in the mysterious “Room Five”, where the motion pictures were secretly developed after Edison famously demanded a device that would do “for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear.”

At this time, Edison was already well informed about the technical developments in the field and had met with Eadweard Muybridge in his West Orange laboratory and visited French physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey in Paris. How much Edison himself contributed to the invention of motion pictures remains unclear, but it is undisputed that he conceived the idea and initiated the experiments that would lead to the so-called Kinetograph, a device that was conceptually based on his Phonograph. This design ultimately proved to be impractical, but familiarized Dickson with the then new emulsion-coated celluloid film sheets.

Inspired by the work of Marey and Demeny at their Station Physiologique in Paris, Dickson soon moved in a different direction. In his Chronophotographe, Marey used a continuous roll of film to produce a sequence of still images, but the lack of film rolls of sufficient length and durability delayed further developments. For Dickson’s work, this problem was solved when John Carbutt’s Keystone Dry Plate Works in Philadelphia started to produce long bands of celluloid film in 1888. One year later, the newly founded Eastman Company in Rochester also introduced a thin, flexible, transparent roll made from celluloid for its Kodak still camera.

Figure 3 a & b: To the left a publicity photograph of a man using the Edison Kinetophone which is equipped with hearing tubes for synchronized sound. To the right a view of Peter Bacigalupi’s San Francisco Kinetoscope and phonograph parlor on Market Street. Both photographs form around 1894-95

Based on this new material – which was finally sensitive enough to capture objects in motion – Dickson and his new assistant William Heise began to develop the Kinetoscope (figs. 3a & b), the first movie machine to use 1 3/8” (34.9mm) film strips. According to film historian Paul C. Spehr, Edison bought film from Eastman Kodak from 1889 until 1893. When Eastman discontinued making celluloid roll film because of manufacturing problems, Edison purchased stock from Blair Camera Co. from 1893 until 1895. Until circa 1895, the film was trimmed to size and perforated by trimming and perforating devices Dickson had designed. In 1896, Eastman also began manufacturing unperforated cine film designed for motion picture work.[3]

Nevertheless – even after roll film had been introduced – there were still a lot of competing formats and a significant difference concerning its application in motion picture and still photography. This is mainly due the fact that formats in still photography are much less complicated than in motion picture film.

Strip film in still photography

Normally, the difference in still camera formats is that of size and shape. With a still camera, the image size is not directly related to the final print format. Still images can be cropped for use without optical duplication, while motion picture images on the screen appear as shot. In still photography, strip film is used in many different sizes (fig. 4) and either delivered as roll film or in cartridges. Confusingly, roll film was originally often referred to as “cartridge” film because of its resemblance to a shotgun cartridge. The original Kodak camera of 1888 was one of the first roll-film cameras – but, since only the Kodak laboratories could process and reload the camera, it was not necessary to specify which kind of roll film was required. This changed with the introduction of the No. 2 Kodak camera in 1889 which could be loaded by the photographer. As different models and sizes of cameras were introduced, the film boxes were marked with the names of the cameras that the roll would fit. By 1908, this system had become difficult to use for ordering film. It was now necessary to specify the image size and the camera the film was to be used in, as not all films for the same size pictures could be used interchangeably.

To simplify this system, it was decided that the daylight-loading roll films on flanged spools would be numbered in the order of introduction, starting with the first Kodak film of this type introduced with the No. 2 Bullet camera in 1895 as number 101. This system was gradually phased in as new film boxes and camera instruction manuals were printed, but the numbers did not appear in Kodak price lists until 1913. Since then roll film has been defined by three figure codes – 127, 116, 120, 110 and so on.

(Fig 4) Chart of the different sheet and roll film formats used in still photography. Double page from the 1933 Zeiss Ikon Camera Catalog C506a

The 135 film-code was used exclusively for still cameras using lengths of 35mm cine film. While the Leica camera popularized the format, several 35mm still cameras used perforated movie film way before the Leitz-Camera was introduced. The first big-selling 35mm still camera was the American Tourist Multiple (fig. 5), which appeared on the market in 1913. The Minigraph, a half-frame small camera, was sold in Germany in 1915 and the patent for the Debrie Sept camera – a combination 35 mm still and movie camera – was introduced in 1918 (the camera was sold from 1922). While there were at least a dozen other 35 mm cameras available by that time, the Leica, which was launched in 1923, was a huge commercial success and came to be associated with the format.

In 1934, when 35mm film in cartridges was introduced with the Kodak Retina camera, number 135 was assigned to this product. This film size could also be used in the Contax and Leica cameras. Daylight-loading spools of film for these two cameras were also offered and were numbered 235 and 435. Over the years, there was a continuous reduction in film size for amateur cameras mainly to reduce the cost of shooting film. Probably the last and smallest format of cameras with film on a roll were the Kodak Pocket Instamatic cameras using 110 film in a cartridge with a frame size of 13mm x 17mm. A different format that Kodak introduced in 1982 was the Disc Camera, which took ten images of 8mm x 10mm on a disc. It was followed by the APS (Advanced Photographic System), which was 24mm wide with the frame 30.2mm by 16.7mm.

(Fig 5) Page form the advertising brochure for the American Tourist Multiple (1913), one of the first cameras to use 35mm cine film

Strip film in cinematography

Although there were a lot of different strip film formats in the pioneer days of cinematography, the 35mm width film soon became the most common one in the industry (fig. 6). However, until 1928, the standard in the UK and the USA was actually 34.9mm (1 3/8”). The imperial measurement remained until the SMPE-produced standards4 made 35mm the prime width measurement. In fact, all the original dimensions were imperial; the number of frames was measured per foot (sixteen) and the film length in feet. So, even up until quite recent times, you purchased 35mm film, and 16mm for that matter, with the length in feet. While 35mm always was referred to as the ‘standard’ format, until 1898 two different types of perforations were used: the one for the Lumière Cinématographe (fig. 6a) with one circular perforation on each side and the Edison standard with 4 perforations (fig. 6b). Also, soon film widths of less than 35mm were introduced. One of the early sub-standard widths was 17.5mm where 35mm was split in half giving twice the running time for the equivalent length in 35mm. Slit 35mm had the same perforation pitch and number of perforations as 35mm but just on one edge.

(Fig 6) Two examples of early 35mm cine-film with different types of perforations (a) Lumière Cinématographe film. (b) Stencil-colored frame of a Pathé Frères film in the Edison standard from around 1900

Other 17.5mm formats had been around since the early days. Hybrid cameras that could be used as both a cine camera and a still camera were also made. The Birtac camera5 that was put on sale in 1899 used 17.5mm film, 35mm cut in half. The Biokam from the Warwick Trading Company was on sale later in 1899 and took 11/16” film with a single perforation in the center of the frame line (fig. 7a). The Biokam was advertised as “A combined Cinematograph and Snap-shot Camera, Printer, Projector, Reverser and Enlarger fitted with two Special Voigtländer lenses.” After the film had been processed, the camera could be converted into a projector by attaching a light source.

The Kino, introduced in 1903 by Ernemann of Dresden, was advertised as “The Amateur’s Cinematograph – Takes the Negative, Prints the Positive, Projects the Finished Picture.” It used 17.5mm film similar to the Biokam but with a taller and slightly narrower perforation (fig. 7b). The Duoscope from 1912 used two perforations on the frame line and could also be operated as a projector (fig. 7c).

(Fig 7) Early 17,5mm amateur film formats. (a) Biokam (1899), (b) Ernemann (1903), (c) Duoscope (1912)

Numerous widths, including ½”, 15mm, 11mm and 21mm were introduced in the early days of the 20th century. Pathé introduced the 28mm film for home use in 1912 (fig. 8a), the same year that Edison promoted his Home Kinetoscope. A special feature of this system was that the 7/8” wide film had three rows of images – this allowed playing a roll of film three times without the need to rewind (fig. 8b).

In 1923, Eastman Kodak decided to introduce a new width for amateur use that would only be available as safety film: 16mm (fig. 9a). The first 16mm film was double perforated. The eventual introduction of sound caused considerable debate on where the sound track should be placed; one of the options was to have the track alongside the picture and continue to use double perforated film. The major disadvantage of this was that silent films could not be shown on the same projector as sound films without changing the aperture plate. It was finally decided that one set of perforations would be removed and replaced with the optical and later the stripe magnetic track; this solved the problem.

(Fig 8) Two early home film formats. (a) A single frame from a 28m Pathé Kok film with asymmetric perforation and (b) frames form an Edison Home Kinetoscope with three rows of images and two rows of perforation.

Pathé had introduced 9.5mm film with one central perforation per frame in late 1923 as part of the Pathé Baby amateur film system (fig. 9b). It was designed to compete with 16mm in practicality und image quality. Due the fact that the film had no perforations on the sides, 9.5mm had almost the same image area as a 16mm frame. Three years later, Pathé also introduced

a 17.5mm wide version of this film that was named Pathé Rural (fig. 9c).

As with still photography, there was also a move towards smaller formats in cinematography for economic reasons. Standard 8mm was introduced in 1932 and was 25ft of 16mm with twice as many perforations that was run through the camera twice, up one side and down the other, the film being split into two lengths that were then joined together end-to-end giving a film 50ft long. The 8mm frame was less than half the 16mm frame as the perforations were the same size. To reduce their size even more, cameras were made to take single width 8mm film. Standard 8mm was replaced in 1965 with Super 8mm with smaller perforations and the film was supplied as 50ft of 8mm film in a cassette.

(Fig 9) 1920s amateur formats. (a) Single perforated 16mm, (b) 9.5mm Pathé Baby and (c) printed 17.5 Pathé Rural film on specially perforated 35mm stock that then is slit in two halves

Wide screen cine formats

In the movie industry, there also was a tendency to use formats larger than 35mm and the quest for widescreen images had been going on since the very early days of the cinema.6 One of the early attempts was RKO’s Natural Vision format using 63mm film (1926) and the 70mm Grandeur film developed by the Fox Film Corporation (1929) – both used commercially on a rather small scale. In parallel, Warner Bros. released some feature films in 65mm Vitascope (1930) and Paramount introduced their Magnafilm and Magnifilm wide screen formats on 56mm. A second wave of wide screen cinema hit the silver screen in the 1950’s: The Todd-AO system (1953) used 65mm camera film and had prints made on 70mm print stock (fig. 11a). MGM also used 65mm camera film and printed onto 70mm film as was the case with Panavision Super 70 and Ultra-Panavision 70 as well.

However, the cost of shooting on 65mm negative and making prints on 70mm print stock (fig. 10) – the additional 5mm was for the magnetic sound track – led to 70mm prints being made by blowing up from a 35mm negative. Whilst not giving any increase in picture quality, the larger format did enable a brighter image on the screen. The desire to have something different and exciting encouraged the invention of the IMAX cinema in the early 1970s. IMAX film is shot on 65mm negative and printed onto 70mm print stock with a frame that was horizontal and fifteen perforations wide. The reels are made up into a single reel that is run through the projector horizontally rather than the usual 35mm vertical transport using what is called a cake stand.

(Fig 10) Single frame of a modern 70mm wide screen film with 5 perforations on each side

But, the extra cost of using larger formats and the improving quality of film again encouraged the use of 35mm. Eventually, the introduction of 35mm widescreen formats using frames with smaller height, three and two perforations high, became more common as a cost saving. In addition, anamorphic lenses were used to increase the screen ratio. Techniscope had frames that were two perforations high using a normal lens and then an anamorphic lens to stretch the image during printing to a normal four perforations high scope frame that was projected through an anamorphic lens.

Cinerama had been brought to the cinema in 1952; this involved a curved screen and three interlocked projectors. It used 35mm film but the image was six perforations high. The success of the enormous screen image led 20th Century-Fox to introduce CinemaScope (fig. 11b). This used 35mm film but with smaller width perforations, known as Fox holes, and the image was anamorphically squeezed to give a ratio of 2.55:1 on the screen. Because this system required unique printing machines and unique projectors it made it very costly for laboratories to print films. The equipment need for cinemas to be able to project these films was expensive too and, therefore, prints were also made on standard stock so that films could be shown on the customary projectors with a ratio of 2.35:1. Fox eventually went over to using standard perforations. There were anamorphic formats introduced all over the world with names like Ultrascope (Germany), Sovscope (USSR) and Cinepanoramic (France) to compete with Cinemascope.[7] The next major step forward was VistaVision from Paramount. This used 35mm film but with the image running horizontally along the film; the image was eight perforations long with a screen ratio of 1.96:1. This again suffered from the problem that cinemas had to be equipped with special projectors so prints were made by reduction and rotation onto 35mm giving a ‘normal’ image with a ratio of 1.85:1.

(Fig 11) Single lens wide screen systems of the 1950s. (a) 70mm Todd-AO system (1953), (b) CinemaScope (1955)

Early color systems

Pioneers in cinematography were also striving to produce color images and, as the only films available were black-and-white, the methods required the use of separations. The world’s first moving color images were shot by Raymond Turner using film 1½” wide with one circular perforation on each side of the frame. He had a camera, projector and perforator made for his use by Alfred Darling of Brighton in 1901 (fig. 12a). A major problem with separations when photographing moving objects is time/parallax error. Objects changing position between the exposure of each separation when the separations are recorded sequentially will cause color fringing when the separations are combined. Efforts to eliminate or reduce this problem led to the introduction of different formats. One solution was to photograph the separations simultaneously by using three lenses on the camera and having three images within the same frame. Other solutions were provided by beam splitting or bi-packing. These eventually replaced the systems that needed three lenses on the projector because of the almost impossibility of getting the three images in register; some pioneers tried using two separations with two images per frame but the result was just as poor. Technicolor used the method of beam splitting to avoid time/parallax errors (fig. 12b). Their early systems used two color separations which were exposed on the film as standard sized frames although one color was upside down compared to the other.

(Fig 12) From left to right: (a) Sequential 3-color separation on 38mm Lee Turner, Positive (1901), (b) Two-color Technicolor negative separated via beam splitter (ca 1922), (c) Two-color Technicolor print with visible bleeding edges in orange-red and cyan-green

When they eventually moved to three color photography, the Technicolor camera used a combination of beam splitting and bi-packing. Bi-packing means running two rolls of film in contact through the gate at the same time. The frames were standard silent 35mm format (fig. 12c). Many color systems were invented – some more successful than others – the majority were variations on the two-color technique. Two that did not use two-color were Dufaycolor and Gasparcolor (figs. 13a - c). Dufay was used both in still photography and motion picture photography. It was first available as a reversal film and then later as a negative/positive system. The film had red, green and blue stripes criss-crossing one another mechanically printed onto the film base which was then coated with a panchromatic emulsion. The film was subsequently exposed through the film base. The major disadvantage was the low level of light that was transmitted though the film. Each ‘pixel’ only transmitted one color reducing the overall brightness. Another disadvantage for motion picture use was the difficulty of printing the negative film without desaturation due to irradiation and reseau image-element spread. Dry D. A. Spencer of the Kodak Research Laboratory invented a ‘depth developer’ which restricted development to the lower layer of the emulsion layer in immediate contact with the reseau, eliminating the problems.[8] Gasparcolor was invented by Hungarian Dr. Bela Gaspar and introduced in 1934; it used dye destruction to produce the three-color image. It was only used as a print film as it was necessary to separately expose each layer from three color separations. However, it was capable of very high color quality.

Kodak produced a lenticular film, Kodacolor, for amateur use in 1928. The base of the film was molded with vertical lenses and the film was exposed through the base with a filter over the lens that had a red, green and blue stripe. The film was black and white reversal. After processing, the film was projected with the same filter over the projector lens. A 35mm print film9 that used the lenticular process was introduced by Kodak in 1937.

(Fig 13) From left to right: (a) Gasparcolor print of Len Lye’s film Colour Flight (1937), (b) Dufaycolor print from the Kodak Film Samples Collection (1940s), (c) Photomicrograph (50x) of a Dufaycolor print

Laboratory formats

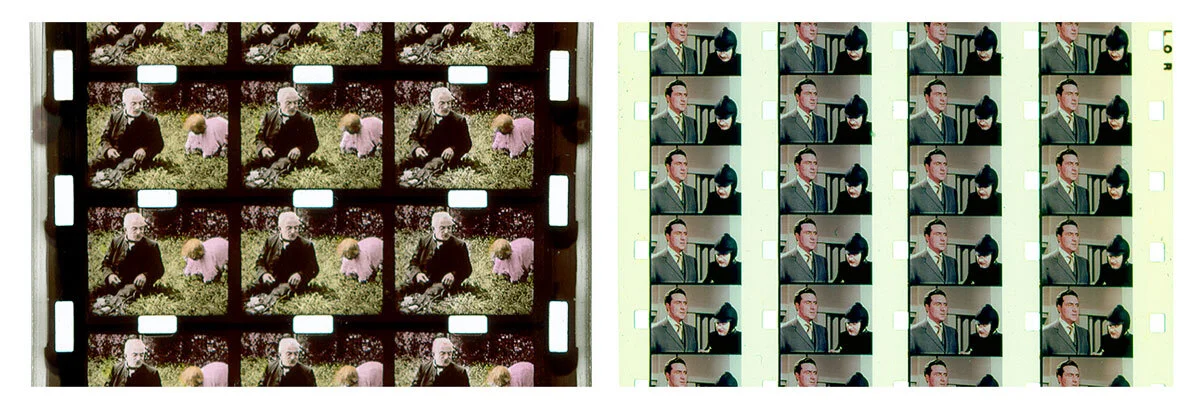

Once sub-standard formats became common for use at home and commercially, laboratories that had processing for only 35mm or 16mm had to find ways for them to produce multiple copies in the small formats. For this purpose, special film stock with multiple perforations according to the desired end-format was produced. In the case of 9.5mm, three rows were printed onto one strip (fig. 14a) of 35mm film and later spliced – for standard 8mm and super 8mm (fig. 14b) four rows were used. Special 16mm printing stock was used either for two rows of standard 8mm or super 8mm, or one row of 9.5mm with the side clearance cut away.

The usual method for printing double 8mm was to use the same technique as in cameras; that is, with the image running from head to tail on one side and tail to head on the other and then splitting the film. The introduction of a magnetic sound stripe for 8mm, led to the manufacture of 8mm stock in the 1:3 format; that is, with both sets of images running from head to tail. The position of the perforations was defined with numbers; the perforations on the left were numbered as one, the two central positions as two and three, and the perforations on the right as four. The 1:3 format enabled the sound to be recorded onto the magnetic stripe of both films simultaneously. 35mm multiple formats were also printed with all the images running in the same direction.

(Fig 14) From left to right: (a) Three row 9.5mm on 35mm reversal color print, (b) Four row super 8mm on 35mm color print

The film specimens (fig. 6 – fig. 14 except for fig. 11) are from the following collections (in alphabetical order): Collection Johann Lurf (A), Collection Brian Pritchard (GB), Department of Film Studies, University of Zurich (CH), George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film (USA), Kodak Film Samples Collection at the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford (GB), Museum of Modern Art (USA), National Film and Sound Archive (AU).

Footnotes

[1] See also: Romana Karla Schuler, Seeing Motion: A History of Visual Perception in Art and Science, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2015.

[2] W.K.L. Dickson and Antonia Dickson, Life and Inventions of Thomas Alva Edison, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1894.

[3] See also: Paul C. Spehr, W.K.L. Dickson: Pioneer Filmmaker, in: Bruce Charles Posner (ed.), Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-garde Film 1893-1941, Anthology Film Archives 2001.

[4] SMPE, Standards Adopted by the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, January 1928, USA.

[5] David Cleveland and Brian Pritchard, How Films Were Made and Shown: Some Aspects of the Technical Side of Motion Picture Film 1895-2015, David Cleveland 2015, 147-186.

[6] See also: Harper Cossar, Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema,The University Press of Kentucky 2010.

[7] David Cleveland and Brian Pritchard 2015 (reference 5), 312.

[8] Adrian Cornwell-Clyne, Colour Cinematography, London 3rd Edition 1951, 290.

[9] J.G. Capstaff, O.E. Miller and L.S. Wilder, ‘The Projection of Lenticular Color-Films’, Journal of Society of Motion Picture Engineers, vol. 28, February 1937, 123-135.